Although fighters and other combat athletes have used the sauna over the years to drop those last few extra pounds of water weight, one of its best uses is for recovery and regeneration.

This is something the Finnish know well. The sauna has been a part of their culture for generations.

The sauna falls into the stimulation category of regeneration because it drives your heart rate up and core temperature up, meaning it’s a form of stress because it activates the stress response system.

:

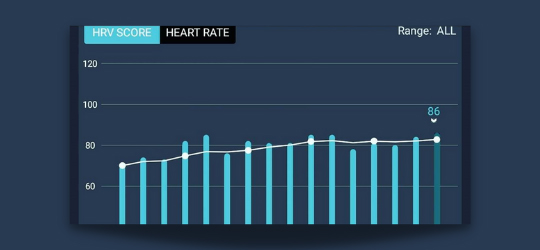

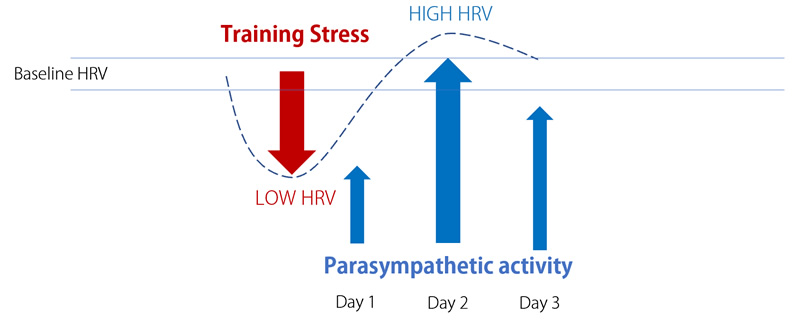

That means it can be particularly effective during periods of intense training where you’re starting to see HRV consistently higher than normal. This can happen during prolonged periods where you’re under more stress than you can effectively recover from.

When this happens, your parasympathetic “rest & recover” system can become burnt out from constantly trying to kick your body into a recovery state.

This is often called parasympathetic overreaching or overtraining.

When you get to this point, it’s common to feel general fatigue, lack of motivation to train, higher HRV, lower resting HR, and lower heart rates during training, excessive sleep, etc.

The sauna works because it provides a very mild sympathetic stimulus that triggers the body’s adaptive mechanisms without placing physical stress on the body.

It’s akin to jump starting a car; it gets things going again.

This is pretty the same as how all stimulation regeneration techniques work, as we’ve discussed in previous lessons.

Why not use this method all the time as a preventive measure for overtraining?

It can be easy to think that using the sauna, or other types of stimulation methods, all the time is a good way to really turbocharge your recovery.

The problem with this idea is that you need a certain amount of daily and weekly stress to force the body to adapt to it and get more fit.

If you are constantly using these types of regeneration methods to promote recovery all the time, you may lose the benefits of the loading.

Remember, stress itself isn’t bad. Without it, you’d never improve.

It’s too much stress for too long, i.e. more than your body can recover from, that’s what you need to avoid.

If you feel like you have to use the sauna or other regeneration methods all the time, you’d probably be better off dialing back the level of stress in the first place.

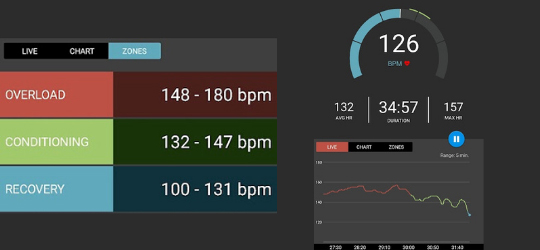

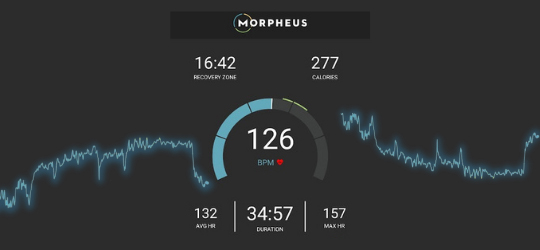

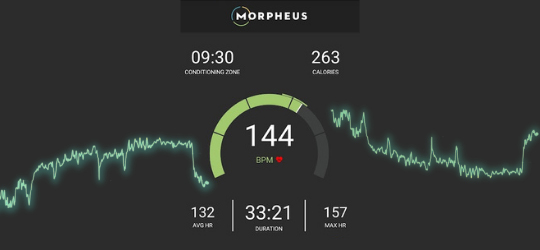

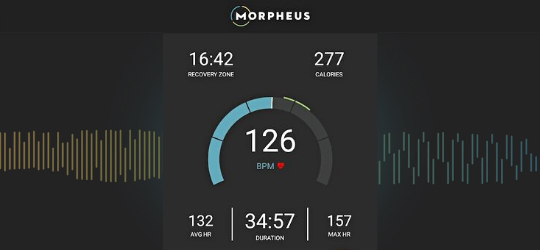

The key is knowing when to use the sauna, as well as getting the dose right, as we’ve covered before. And that’s why we pay attention to your Morpheus recovery score and trends in your HRV.

Using The Sauna the Right Way

To get the most out of the sauna, it’s important to be pretty specific in how you use it.

Just hopping in for a few minutes and getting out probably won’t do a whole lot for stimulating regeneration.

Make sure to use a dry sauna for this method, not a steam room, wet sauna, or infrared sauna. The hotter you can get it, the better–preferably over 200° F (93.3°C).

Next, to manipulate your body temperature, it’s valuable to have shower close by to really do the method correctly. Fortunately, most saunas tend to be in locker rooms or near a shower.

Assuming you have a dry sauna that gets very hot and a nearby shower, you’ve got everything you need to use the sauna to promote recovery so you can keep training or get back to it.

Note that if you overuse any regeneration method by doing it all the time, it will lose its effectiveness.

That’s why we’re covering a range of regeneration methods in these lessons. By the end of this 30-day challenge, you’ll know how to use different ones depending on the situation.

You can use the sauna for a week or two at a time, then use something else the next time you need to promote recovery.

The Ultimate Sauna Recovery Method

What I’m going to share with you is an old-school Russian sauna method. It takes some time to do, but it’s an effective line of defense against chronic stress when you need it.

Try to follow these specific guidelines as closely as possible for the greatest recovery benefit:

- Preheat the sauna to the highest temperature possible, at least 200° F (93.3°C) is preferable

- Get in the sauna and stay until you first break a sweat, then get out

- Rinse off for 5-10 seconds in lukewarm water, then get out of the shower, pat yourself off, wrap a towel around yourself, and sit down for 2-3 minutes

- Get back in the sauna and stay for 5-10 minutes. The original method calls for staying in until 150 drops of sweat have dripped off your face. For most people, this is 5-10 minutes

- Take another shower, this time make it as cold as possible, and stay in it for 30 seconds. Let the water cover your head completely the entire time

- Get out of the shower, pat yourself dry, wrap a towel around yourself, and sit down and relax until you stop sweating completely and your skin is dry. This typically takes anywhere from 3-10 minutes

- Return to the sauna and stay in for 10-15 minutes, then get out

- Repeat steps 5 and 6

- Get back in the sauna for another 10-15 minutes, then get out

- Take another shower, this time make it fairly warm, and stay in for 1-2 minutes

- Dry yourself completely off, lay down and relax for 5-10 minutes

The reason this method is so effective is because it manipulates heat and body temperature to stimulate both the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems in sequence. When used the right way, it can be an incredibly effective way to boost your recovery.

Action step:

Identify the most convenient sauna/shower for you to use in your area. Common places include large gyms, bath houses/spas, apartment complexes, etc.

If your Morpheus recovery data shows you’d benefit from regeneration methods, (your HRV is climbing and your resting HR is dropping in spite of feeling chronically fatigued/lethargic), give the sauna method a try.