To understand the benefits of threshold training, we have to take a minute for a mini-lesson on how our body turns glucose (blood sugar) into ATP – the energy currency all our cells run on.

Don’t worry, it’ll be a short lesson and there’s no quiz at the end.

The first step of this process is known as glycolysis. Because there are only a few chemical steps and it doesn’t require oxygen, it’s a relatively fast process.

The downside, however, is that it also doesn’t produce very much ATP.

Along with the ATP, the other main end product of glycolysis is another molecule called pyruvate.

The next step is where things get interesting.

When your body has enough oxygen being delivered to your muscles, pyruvate is transported into your mitochondria (the energy power plants in your cells) and sent through a much longer series of chemical steps.

These steps are relatively slow, but they produce a lot of ATP.

When there is not enough oxygen available, pyruvate instead ends up as a different molecule called lactate—often used interchangeably with lactic acidemd .

Though there is some debate within the scientific community as to whether or not lactic acid ever technically forms in cells, it’s universally agreed upon that lactate is not what makes you tired or sore.

Instead, lactate is transported from the muscle cells that don’t have enough oxygen into other muscle fibers and even places like the heart, where oxygen is much more abundant.

With oxygen, lactate is then used to create more ATP.

So to recap:

- When your body breaks down glucose aerobically (with oxygen) you end up with a lot of ATP, but it’s a slow process because there are a lot of chemical steps that have to happen.

- When your body breaks down glucose anaerobically (without oxygen), it’s a much faster process, but it only produces a relatively small amount of ATP. At the same time, this process also leads to the formation of lactate.

What is the anaerobic threshold, anyway?

Hopefully you followed along with my little chemistry lesson, because it makes the concept of the anaerobic threshold much easier to understand.

The main thing to know is that at relatively low to moderate intensities, the body is able to generate all, or at least most, of the energy it needs aerobically because it has enough oxygen available to turn both fat and glucose into ATP.

As intensity and the demand for energy increases, at some point, the body has to start to tap into the anaerobic side.

As an example, let’s say your body can produce enough oxygen to allow you to run at 8mph purely through aerobic metabolism.

When you have to run 9, 10, or 11 mph, your body has to get the extra energy from the anaerobic side through glycolysis.

When this happens, the amount of lactate in the blood starts to increase.

All this really means is that more and more glucose is being broken down anaerobically and the aerobic system can’t keep up.

The faster you run, the more anaerobic energy you’ll need and the faster lactate will start to accumulate in the blood.

The point at which there is a rapid increase in lactate above a certain level is what is known as the anaerobic threshold. Because it’s based on lactate levels, it’s also often referred to as the lactate threshold.

Regardless of what it’s called, the simplest way to think about the threshold is that it’s the tipping point where lactate accumulates because the aerobic system isn’t able to produce as much energy as you need by itself.

As you hit the threshold and above, your body is producing an ever increasing amount of energy from the anaerobic side of the equation.

This is important because the simple and unavoidable rule of our biology is that the more we have to rely on anaerobically-driven energy, the faster we fatigue.

The anaerobic threshold and performance

All things being equal, if you have a higher anaerobic threshold, it means you have better aerobic fitness and you’ll be able to sustain higher speeds and generate more power for longer.

A person with an anaerobic threshold of 180bpm will generally be able to hold a higher pace than someone with a threshold of only 150bpm, for example.

This is why how fast someone can run at their anaerobic threshold is one of the best predictors of performance in endurance sports. Far better than another common aerobic marker, VO2 max.

An important thing to note, however, is that even though a single heart rate or speed is commonly used to denote the threshold, this is a bit of a misnomer that’s based on older research.

There is not one single heart rate where all of a sudden your energy production shifts dramatically. Instead, it’s more accurate to think of a heart rate range where this occurs rather than at a single point.

Where is your threshold?

The goal of the threshold method is to help improve your aerobic fitness to the point that it requires less energy from the anaerobic energy pathway to produce the same speed or power.

If you start out being able to run 9mph at your threshold for example, you’ll quickly fatigue after a few minutes there. Even faster if you go up to 10mph, 11mph or more.

If you are able to improve your aerobic fitness and increase your speed at your threshold up to 11mph, then you’d be able to sustain that same 9mph for much longer than before.

One of the most effective ways to train to develop this ability is to train within the range of your anaerobic threshold.

The main challenge with this, however, is that trying to determine exactly where this is requires getting tested in a lab and even then, it’s not as much of an exact science as many people make it out to be.

Your threshold also changes dramatically depending on the exercise that you’re doing.

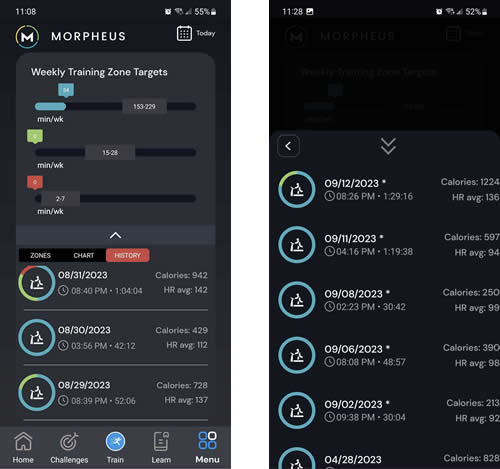

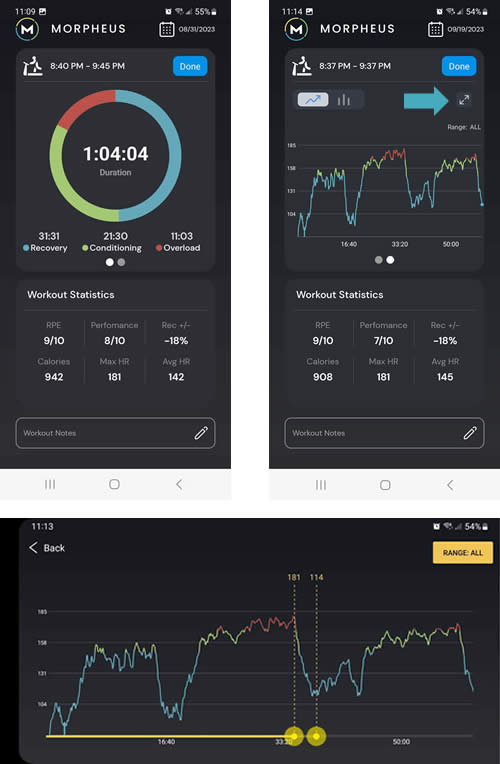

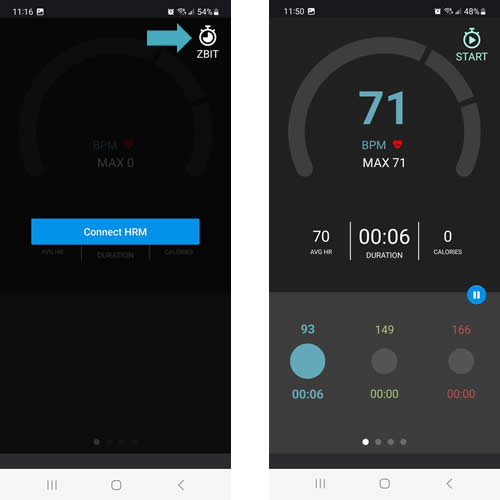

Fortunately, unless you’re a competitive endurance athlete, it’s not really necessary to get an exact threshold anyway. The Morpheus heart rate zones were designed to help you train at intensities around your threshold without the need for specific testing.

To do this, make sure you’ve selected the right fitness level and either input your max heart rate, or let Morpheus do this for you. In the same settings, you can enter your threshold if you do know what it is, but if not, simply leave it blank.

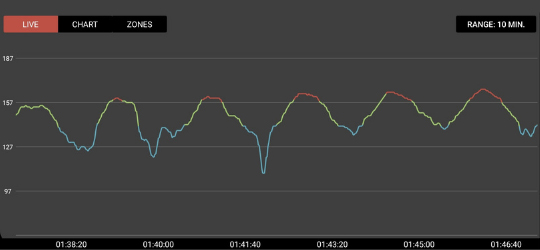

From there, you can do two levels of threshold training: green and red.

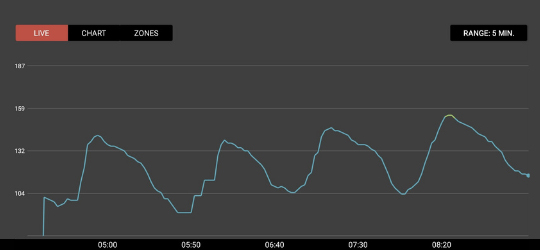

For most people, as long as their recovery score is somewhere between about 85-95% recovery, then training around the top of the green zone will put them just below or at their threshold.

This should be a pace that’s challenging, but one that’s sustainable for up to 10-15 minutes without significant fatigue.

Moving up to the bottom of the red zone should then be just above their threshold. This should be a pace that’s generally sustainable for much less time, more like 3-5 minutes, before fatigue starts to set in and forces you to slow down.

How to incorporate threshold training into your program

As with other higher intensity methods, this type of training is best suited for people that already have a foundation of fitness to begin with. Very generally speaking, this means an HRV in the mid-70s or above in Morpheus.

If you’re below that, just starting out, or coming back from a layoff, lower intensity methods should be used first.

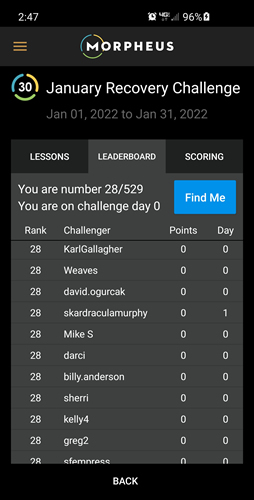

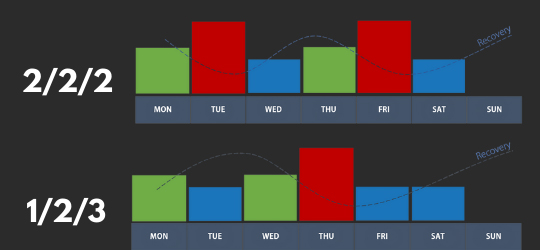

Threshold training is effective when it’s done 1-2 times per week. This is often the right frequency to stimulate the body to improve, without pushing it to the point that it can’t recover.

When doing green thresholds, a good total range within a workout is typically between 10-30 total minutes. This can be broken up into intervals of anywhere from 5-10 minutes at a time, with 2-3 minutes of active recovery in between.

Because red thresholds are higher intensity, you’ll want to shoot for less total time. Anywhere from about 5-12 total minutes per workout is all you need.

You’ll want to break these up into shorter intervals as well. Alternating 2-3 minutes of work with 1-2 minutes of active recovery is a good guideline to start with.