Recovery has become a buzzword in fitness over the last few years, but what does it really mean?

Does having a higher recovery score mean you can train hard and a lower recovery score means you should stay at home?

Is the best way to recover faster to just rest and get more sleep?

To get to the bottom of what recovery is and how Morpheus works, we have to go back to two things we talked about in yesterday’s lesson: stress and energy.

How the body adapts to stress (and why it’s so important)

At the very heart of fitness (and survival itself) is the concept of adaptability.

In simplest terms, adaptation is the process the body goes through to become more fit to handle the demands of its environment. In the wild, this also means it’s better equipped to survive.

This is how training works.

By lifting weights, doing cardiovascular conditioning, practicing a skill, playing a sport, etc., you are creating a specific environment that your body has to adapt to.

You lift heavy weights, it gets stronger. You run long distances, it gets more efficient. You practice a specific lift or movement, your technique gets better.

This is nothing more than the body’s adaptive mechanisms at work. There are two parts to this process: stress and recovery.

When you’re training, you’re putting your body under stress.

This means your stress-response system is working hard to crank up energy production. The more force and power your muscles produce, the more energy they need.

Once the workout is over, that’s when recovery begins.

The most important thing to understand about recovery is that just like stress, it’s all about energy.

In this case, the body needs energy to repair and rebuild stressed muscle tissue. To add new mitochondria (the power plants of our cells). To create and reinforce the neural pathways that improve our technique and skill.

This use of energy is what we call recovery.

In other words, recovery is the process of using energy to adapt to the stress of our environment.

When it comes to fitness, it’s this process that turns the workouts we do into improvements in strength, power, hypertrophy, body comp, skill, and performance.

The problem with recovery

Your body is constantly through periods where it’s put under stress, followed by time where it can recover from that stress. This is what we call a stress-recovery cycle.

In a perfect world, you’d have all the energy you need to fully recover and adapt to each period of stress.

You’d make constant improvements in your fitness. You’d never feel tired, run down, or lack the motivation to get off the couch. You’d never get sick.

The problem is that we don’t live in that perfect world.

In the real world, our bodies can only produce a fixed amount of energy each day no matter how much we eat or sleep.

The mental stress of life can add up quickly. We can convince ourselves that we need to do one high intensity workout after another.

It can be all too easy to put our body under more mental and physical stress than it has the energy to adapt to. When this happens, we put ourselves into a recovery debt.

If a recovery debt is small, it most often leads to frustrating plateaus where you’re putting in the work, but not seeing any improvement. Unfortunately, this is where a lot of people in fitness get stuck.

Over time, if the balance between stress and recovery isn’t fixed, the body will fight back.

You’ll start to feel more fatigued all the time. You’ll be less motivated to go to the gym and more likely to get injured if you do. You’ll crave foods you know you shouldn’t eat.

Sound familiar? Almost everyone that’s trained hard has experienced this at one time or another.

Fortunately, there’s an easy way to prevent all this…

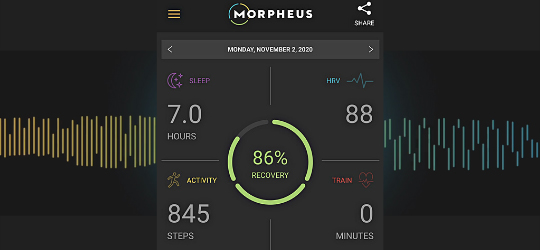

The Morpheus recovery score

A lot of people have been led to believe that a low recovery score on an app means that their body can’t train hard or perform well.

They are often confused when they get this low recovery score even though they feel just fine. Or, they are surprised when they choose to train hard anyway and then hit a PR.

The reason this happens isn’t necessarily because the recovery score is wrong.

It’s because no matter what anyone tells you, a recovery score is not a predictor of what your body is capable of, or how well it will perform at any given time.

Instead, the most accurate way to understand a recovery score, particularly the one Morpheus gives you, is as a gauge of the balance between the amount of energy you’ve been spending on stress vs. recovery over the last few days (or longer).

If your recovery score is low on a given day, it doesn’t mean that you can’t train hard or put your body under more stress.

It just means that if you do, it’ll take even more energy and even longer to fully recover and adapt to all the stress you’ve been throwing at your body lately.

Getting yourself into debt recovery doesn’t happen in a single day.

It’s when you continue to add stress on top of stress, without allowing enough time and energy to go towards recovery, that bad things happen and you pay the price.

When your recovery score is consistently low, it’s a sign that your body has been spending more time and energy dealing with stress than recovering from it.

Because it’s when your body is recovering that gains in fitness are being made, this also means you’re leaving results on the table.

Using the Morpheus recovery score to help guide your training is the key to understanding the difference between what you can do on a given day and what you should do over the long run to reach your goals.

Over the rest of the challenge, you’ll learn more about how all the different areas of life, from sleep, to nutrition, to mental stress, impact the balance between stress and recovery.

Action step

It’s a relatively new idea in the research that our bodies are limited to producing a finite amount of energy in a 24 hour period, but it has profound implications.

The story of how this was discovered is a fascinating one leading back to a hunter-gatherer tribe in Africa called the Hadza.

To learn more, look up Dr. Herman Pontzer and read the story of how he developed this new theory called the “Constrained Model of Total Energy Expenditure”